Beyond the Pod: Why wasmCloud and WebAssembly Might Be the Next Evolution of the Platform

Over the past few months I have invested some time to contribute to an open source project I find fascinating: wasmCloud. As a platform engineer and architect, I am very familiar with how software platforms are typically built in practice. However, with the ubiquity of Kubernetes, you run the risk to being stuck in the "doing it the Kubernetes way" line of thinking. But then again, are there any better ways? This is where wasmCloud caught my attention. A modern platform building on proven concepts from Kubernetes, but with some significant differences. In this article I want to introduce wasmCloud, how it compares to Kubernetes, what its internal architecture looks like, and what ideas are, in my humble opinion, a step up from "the Kubernetes way of things".

Before getting started, I need to get some things out of the way. This article will make quite a few comparisons to Kubernetes and bytecode interpreters like the JVM. If you are unfamiliar with these technologies, it might make sense to have a short look at what these are. Considering you clicked on this article, I am however guessing that you are familiar with them and have some experience in platform engineering practices, either as a poweruser of a platform, or as a designer and developer of one.

Moreover, I want to thank the company I work for, ipt, for allowing me to invest time to learn about new technologies such as wasmCloud. Not only is contributing to open source a great way to pay back a community powering the modern world, it is also a huge passion of mine. Being able to help the development of such projects during paid worktime enables me to learn so much on emerging technologies, and maybe help build the revolutionary tools of tomorrow.

So... wasmCloud!? I have been interested in WebAssembly ever since it promised to replace JavaScript, a language I personally consider as extremely poorly designed (someone once told me it was designed in three days, so no wonder there). While WebAssembly is very far from doing anything close to replacing JavaScript in the browser, it has evolved into something else: an application runtime and a potential replacement for containers.

WebAssembly as a Platform Foundation

Modern platforms nearly all build on top of containers as their foundational element to run executable code. This is a logical evolution from Docker's meteoric growth, and the ecosystem that grew around its open standards (such as the OCI - Open Container Initiative). While containers provide a huge step in terms of ease of use, standardization, and security compared to shipping raw artefacts to virtual machines, as was the case before them, they do have some shortcomings.

First and foremost, containers are not composable. In part due to their flexibility, they do not offer standard ways of expressing how the world should interact with them at runtime, or what they rely on to perform their functionality. This means that containers are typically deployed as REST-based microservices, where containers communicate with one another over a network using APIs agreed upon outside of the container standards. This lack of standardization makes building reusable components more challenging than it has to be. Moreover, each container essentially needs a server, authentication, authorization, and more to run. This results in quite some waste in the compute density of the platform, with lots of compute wasted on boilerplate.

Moreover, while containers are a huge step in the right direction in terms of security, they are not quite as secure as most people are led to believe. Containers are "allow by default" constructs, which take quite some work to properly harden.

Finally, due to how containers are typically built, their startup times are not that great. It is not abnormal to see container start times in the dozens of seconds. This does not bother people very much because containers are mostly used to run long running processes (since we need these REST APIs everywhere). However, a large part of containers are mostly idle, waiting for some API request to come in. If one considers that workloads could be called (and thus the process started) only when needed, startup times over 100ms is considered slow.

This is where WebAssembly comes it. WebAssembly addresses these challenges. Composability is addressed by the component model.

WebAssembly: The Component Model

The component model is a way that WebAssembly modules can be built with metadata attached to them which describe their imports and exports based on a rich type system. Moreover, they are composable such that a new component can be built from existing components as long as the imports of one are satisfied by the exports of another. This means that components can interact with one another via direct method/function calls, whose specification is fully standardized. This interface specification is declared in a language known as the WebAssembly Interface Types (WIT) language. An example of a WIT specification of a component relying on a system clock can be seen below:

package wasi-example:clocks;

world mycomponent {

import wall-clock;

}

interface wall-clock {

record datetime {

seconds: u64,

nanoseconds: u32,

}

now: func() -> datetime;

resolution: func() -> datetime;

}WIT can be compared to the Interface Definition Language (IDL) from gRPC but for wasm components.

This declaration says that the component relies on an interface wall-clock (it imports the

interface) which defines two functions: now and resolution. Both take no arguments and return a

datetime object consisting of a seconds and nanoseconds field. This component could then be

composed with any other component which exports this wall-clock interface.

If this were a container which would rely on accessing some API, we would need to read a non-standardized documentation of the container image, and then read up on other containers to ensure they provide APIs that match the ones called by the first container.

The WebAssembly component model can essentially be seen as a form of contract-based programming to formalize interfaces between WebAssembly core modules.

WebAssembly: Secure by Default

Whereas containers provide some form of security by namespacing processes and filesystems, WebAssembly actually sandboxes modules such that they cannot affect one another, or the host they run on. By default a WebAssembly module cannot perform any privileged action and needs to be granted explicit permission. I will not dive deeper into the details of this or I might loose myself in a rant on how software security in the modern day and age is abysmal.

WebAssembly: Performance

WebAssembly's main goal is performance. This means that WebAssembly modules run fast, but also that loading modules and starting them is much faster than containers. This has proven to be very useful already, for instance in use cases such as serverless computing, where hyperscalers heavily rely on WebAssembly as a runtime to reduce cold start times, and reduce the delay in function calls.

Considering the idea to avoid having long running servers providing REST APIs and move to raw function calls on short running modules, having extremely short start times is imperative.

Alright, so we can see that WebAssembly can be a great choice for the foundation runtime of a platform. So where are platforms leveraging this? Well, actually, quite some "platforms" leverage this idea already. For instance, SpinKube does exactly this, enabling to run WebAssembly functions on Kubernetes. However, you still interact with these functions via a REST call. Another example is Kubewarden, leveraging WebAssembly modules to evaluate policies. While some might argue that this is not a platform, Kubewarden provides a runtime for arbitrary programs, including their scheduling and deployment. Sounds like a platform to me.

Finally: wasmCloud! wasmCloud is probably what people would consider the closest to a full blown platform to run WebAssembly modules. In other words, what Kubernetes is to containers, wasmCloud is to WebAssembly components. It provides a way to deploy, schedule, link, and lifecycle WebAssembly components on a distributed platform.

wasmCloud Architecture

Let us look at the wasmCloud architecture a little.

This section will contain quite a few comparisons to Kubernetes concepts.

Generally, the wasmCloud architecture can be seen as quite similar to the Kubernetes architecture, with the difference being that wasmCloud does not provide as much flexibility in swapping out building blocks as Kubernetes does. This makes sense as it is a more nascent technology and is currently more opinionated.

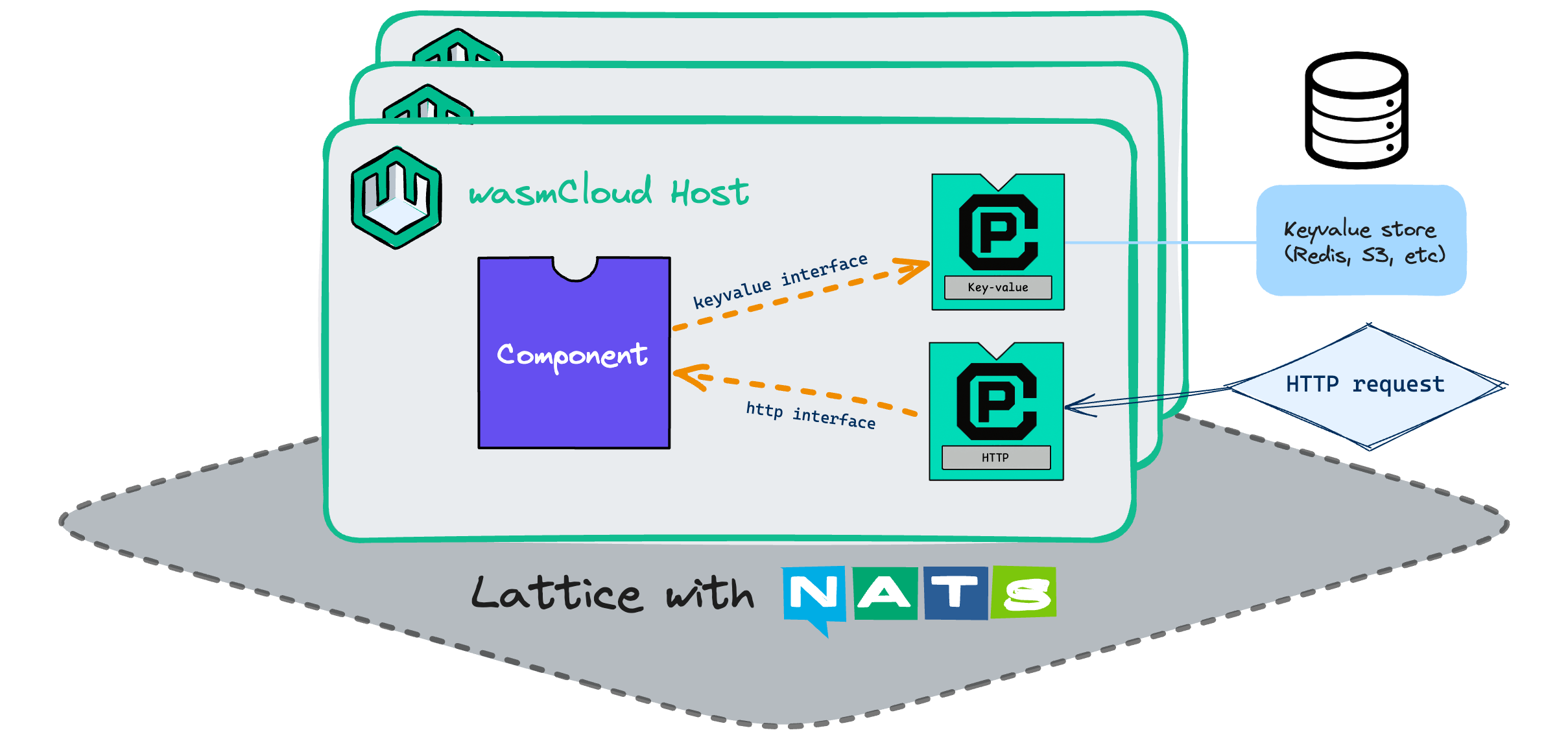

As a reference, here is the diagram wasmCloud uses to provide an overview of the platform:

An overview of the wasmCloud platform

As one can see, the architecture is essentially a set of hosts connected via a so called "lattice". Thus, the architecture distributes the runtime over a set of compute instances in order to achieve resilience against hardware/compute failures. The principle is identical to the one from Kubernetes, providing a cluster in order to be able to quickly shift payloads on the platform to different nodes in case of node failures.

Hosts

wasmCloud hosts are the foundation of the compute platform that is provided. They are the equivalent of Kubernetes nodes and provide a WebAssembly runtime for components to run on. Just as with Kubernetes nodes, application developers will rarely need to worry about the hosts other than for deployment affinities and the like.

In practice, hosts can be anything from a virtual machine, an IoT device, or even a pod running on Kubernetes. In fact, hosting wasmCloud on Kubernetes is a relatively straight forward way to get started with the technology, providing wasmCloud as an application runtime, while providing services via Kubernetes.

Lattice

The wasmCloud lattice is its networking layer. This can seem a bit strange when considering that this a NATS instance.

For those unfamiliar with NATS: it is an event streaming component similar to Kafka, but provides additional features such as a key values store, an object store, and publish-subscribe capabilities.

Having a NATS instance as the "networking layer" confused me quite a lot at first. However, one has to remember that thanks to the component model, we no longer require HTTP/TCP network calls for our components to interact with one another. Thus we don't necessarily need an IP to address a component we want to reach. Of course NATS itself will require a physical network to run on in order to distribute events to its different instances, but wasmCloud then only needs to use NATS.

Essentially, every component exposing a function becomes a subscriber to a queue for this function on NATS. Other components can then call this function via wRPC (gRPC for WebAssembly) by publishing a call to some subject. This is quite different from Kubernetes networking, where calls need to know the location of the callee in the network. Using a subject-based addressing model simplifies deployment and improves scaling and resilience.

As a user of wasmCloud, you do not need to worry about this though. How function calls are preformed under the hood is abstracted away from the user.

This distributed networking aspect is one of the superpowers of wasmCloud, as one does not need to worry about how to address a component on the platform. However, it can also introduce strange behaviour in some cases. For instance, on Kubernetes, it's common sense that a HTTP call to a different pod running on the cluster can fail. On wasmCloud however, if the interface we are calling from a different component returns some type, we use the component like a raw function call in our components code. What if that call fails, not because of the called component but due to a networking issue? In the current implementation of wasmCloud this will lead to a panic in the caller. As this is typically not the desired outcome, efforts are underway to design an adapted way how the interfaces need to be designed to handle failures in the transport layer. On top of that, function calls might change such that might avoid using NATS as a transport layer if the component being called in on the same host and the caller.

Capabilities

This is where Kubernetes and wasmCloud start differing in their philosophy. Thanks to the standardized way interfaces can be declared in the component model, one can describe an abstract interface which provides some functionality, without providing an implementation. This is what capabilities are. They are abstract interfaces that describe some useful functionality, such as reading and writing to a key value store, or retrieving some sensitive information from a secured environment. These capabilities are published on wasmCloud for applications to use.

An application developer can then write a component that makes use of that interface if he/she needs that functionality. He/she does not need to worry about how this capability is implemented. He relies on the "contract" provided by the capability.

In my opinion, while this is quite challenging to grasp initially, this is what makes wasmCloud so promising. Having worked on many platforms in the past, the main challenge is always how additional services can be provided on top of raw platforms such as Kubernetes in a way that makes then highly standardized while easily consumable. In the current state of platform engineering, this quickly becomes a question of good product management. Unfortunately, doing this correctly is surprisingly difficult. Capabilities provide a technical solution to this, with the only limitation being complete incompatibility with existing software.

Providers

A provider is a specific implementation of a capability. For instance, taking the example of the capability enabling the reading and writing to a key value store, a provider might implement this by having a ValKey instance backing the capability. Another provider might implement the very same capability using NATS, Redis, or even an in-memory key-value store.

Abstracting the provider away from the consumer via a capability enables the platform to swap providers based on needs. Of course performing such a swap might be quite complex, for instance involving a data migration from NATS to ValKey. However, the beauty is that the applications do not require any changes as would be the case in traditional platforms.

It should be noted that the provider might run completely outside of wasmCloud itself. However, wasmCloud also provides internal providers that are backed into the hosts themselves, providing functionality such as logging or randomness.

Components

Components refer to the WebAssembly payload that contain your business logic. In the traditional sense, this is your application. However, in wasmCloud lingo, an application is a set of interlinked components including all information about what capabilities they require.

Applications

Applications are an abstraction enabling to declaratively define a combination of components, capabilities, and providers together into a deployable unit. Applications are based on the open application model (OAM) and should thus look quite familiar to people working with Kubernetes. In terms of definition, they are similar to a Kubernetes Deployment, describing not only the deployment unit (component or pod in the Kubernetes context), but also its replication, affinities, links to capabilities, etc.

It should be noted that in wasmCloud v2, applications are re-worked to be much more closely modelled after Kubernetes Deployments and ReplicaSets. Version 2 drops the idea of Applications alltogether and uses

Workload,WorkloadReplicaSets, andWorkloadDeploymentsobjects. These are also no longer linked to the OAM. In all likelihood we will write another blog post showcasing the capabilities of composition provided by version 2 in the future.

wadm

The wasmCloud Application Deployment Manager (wadm) manages Applications. It can be seen as the deployment controller from Kubernetes for wasmCloud Applications. It essentially orchestrates the deployment of components, capabilities, their links, etc. on the platform. This construct will also be dropped with wasmCloud version 2.

Verdict

With a decent understanding of the architecture we can now get an idea of the uses of wasmCloud in the real world. While I have not yet run anything productive on wasmCloud, I have played with the platform a lot over the past few months, and have come to really appreciate some of its innovative ideas.

Thus, to summarise my experience: wasmCloud is a relatively new platform and provides interesting new approaches to how inter-component communication can be modeled. On top of that, it does it while building on open standards such as WebAssembly and the component model, such that the business logic of your application remains portable. While these new concepts are very promising, wasmCloud still suffers from a couple drawbacks:

- For people unfamiliar with WebAssembly, it has a quite steep learning curve. This is highly accentuated for people unfamiliar with existing platforms such as Kubernetes.

- The set of supported providers and capabilities is extremely small to date. This will of course grow as adoption increases, but currently early adopters will have to write their own providers most of the time and will not be able to rely on third-party components.

- As wasmCloud shifts more responsibility to the platform level, it will require a strong platform team to operate this with low developer friction. This can be an issue as finding highly skilled platform engineers is quite difficult at the moment. However, the team behind wasmCloud is focused on making application delivery as frictionless as possible.

- Finally, I am not sure I currently understand the security model wasmCloud uses to authenticate and authorize calls between components. While I am not sure this is a drawback, it does not yet feel as intuitive as Kubernetes simple yet relatively powerful RBAC. I will have to dive deeper into this to have a final opinion on it though (another blog post might follow on this).